Meet the Animals

Elk

(Cervus canadensis)

Elk range in woods and forest edges, eating plants, leaves and grasses. During the fall rut, males make impressive bugling calls to establish dominance and attract females. Also called wapiti, this large member of the deer family was successfully reintroduced to Great Smoky Mountains National Park in 2001. The original herd has now splintered to areas outside the park boundary. As elk continue to move out of the park, more are hit and killed on roadways in East Tennessee and Western North Carolina. Some are badly injured and have to suffer until they die unless wildlife biologists can find them and put them out of their misery. Because a mature bull elk can weigh more than 700 pounds, a vehicle collision with an elk is definitely a safety hazard for humans.

Photo courtesy of Joye Ardyn Durham

American Black Bear

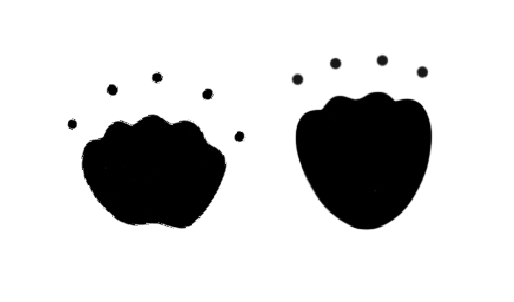

(Ursus americanus)

Black bears are strong, smart, and love their favorite scratch trees. They also enjoy flipping over rocks and tearing into rotting logs in search of insects and other small animals. Great Smoky Mountains National Park is the largest protected black bear habitat in the eastern US, with 1,600 bears, less than two per square mile. Not all are black; they can also be brown, cinnamon, white, or blonde. Black bears love to feast on white oak acorns and bear corn, and adult bears will even eat baby deer. While a mother bear can scale the tall barriers that divide many highways, her cubs may not be able to get a grip on the slick concrete. Both mother and babies often get hit as they try to solve the problem.

Photo courtesy of Joye Ardyn Durham

White-tailed Deer

(Odocoileus virginianus)

Deer are common not just in North America, but on many continents. White-tailed deer thrive when forests are converted to farmland. Mother deer often leave their fawns alone for several hours at a time while foraging for food. The fawns lie still, flat against the forest floor, with necks outstretched, and their spotted coats provide the perfect camouflage. The babies have almost no scent, so predators such as bear, coyote, fox, and bobcat will likely not detect them. Because there are so many of them moving on the landscape, white-tailed deer are the large animal we most commonly see hit and killed crossing highways. Like other large mammals they can’t always see over tall highway median barriers, so they may successfully cross one side of the highway, but not the other.

Photo courtesy of Henry Weinberg

Bobcat

(Lynx rufus)

The bobcat can be identified by its “bobbed” tail that is only about six inches long and tipped with black. The underside of the tail is bright white, and when raised signals to the female bobcat’s kittens that it is safe to move about the forest. While it may look like a cute housecat with its tufted ears and white underbelly, a full-grown adult bobcat weighs in at 30 pounds and will catch prey up to three times its own weight, but prefers rabbits and hares. In addition to hissing, growling, and emitting a sound that some compare to the cry of a human baby, bobcats do actually purr.

Photo courtesy of Marshal Hedin

Red Fox

(Vulpes Vulpes)

The red fox is the largest member of the fox family, and can be found across North America, Europe, Asia, and parts of Africa. They are also hit and killed on roads on all of these continents. Like coyotes, they dig underground dens to birth and raise their young pups. Although this species is known for its bright red fur, the pups are brown or grey when born, but change to red within a month. Foxes generally run in pairs or with a family group. They have long played important roles in human folklore and mythology. Red foxes dine mostly on small rodents, but will also eat berries, insects, and birds, as well as raccoons, squirrels, and opossums, among many other species. They have impressive hearing and can locate rodents digging several inches underground.

Photo courtesy of Emmanuel Keller

Coyote

(Canis latrans)

In the past coyotes normally lived in the more arid, open western two-thirds of North America. Human activities like forest clearing and removal of predators (like the eastern cougar) and competitors (such as the gray wolf and red wolf) gave coyotes a chance to expand their natural range. Coyotes are opportunistic feeders and have an amazingly diverse diet that includes rodents, rabbits, deer, birds, frogs, snakes, carrion, insects, fruits and berries, and grasses. While coyotes generally do not form relationships outside of their species, there is evidence that they occasionally travel and hunt with badgers.

Photo courtesy of Connar L'Ecuyer

Woodchuck

(Marmota monax)

Also known as groundhogs, woodchucks can often be seen grazing very close to busy roadways, sometimes standing up on their hind legs, seemingly unruffled by the noise and speed of traffic. This is simply because some of the best food grows close to the roadway, made extra juicy from water running off the concrete and into the side of the road. Often their daredevil antics cost them their lives. Woodchucks form extensive underground burrow systems. When hibernating, their body temperature can reach as low as 32 degrees and their breathing slows to as few as two breaths per minute. Also called whistle pigs, groundhogs are related to western marmots and prairie dogs, and although more solitary in comparison share a similar predator warning system with their whistling.

Photo courtesy of Tim Parker

Eastern Gray Squirrel

(Sciurus carolinensis)

Eastern gray squirrels are found in wooded areas with many types of trees that provide the nuts they crave. They make two types of nests: traditional cavity nests and leaf nests, which are built by young squirrels. When it comes to crossing roads, squirrels can make jerky movements and suddenly change direction as if not being able to decide which way to go. This often leads to them getting hit and killed, and may be why, if we cannot depend on someone, we say that person is “squirrely.” Gray squirrels are an abundant food source within the forest ecosystem for many species, including coyotes, red foxes, red-tailed hawks, and bobcats.

Photo courtesy of Warren Bielenberg

Red-tailed Hawk

(Buteo jamaicensis)

The red-tailed hawk is one of the largest members of the hawk family. Adults can have a wingspan of nearly five feet. Hawks circle high above roadways looking for prey such as squirrels and snakes. They soar especially high in the late afternoon, taking advantage of thermals rising from the sun-warmed land below. They emit a hoarse, descending scream-like kee-eeeee-arr. Even though they can fly, hawks that swoop into traffic to snatch a meal can be killed in an instant. If you look up next time you see a red-tailed hawk above the road, watch for their red tail feathers shining in the sun.

Photo courtesy of Karen Wilkinson

Barred Owl

(Strix varia)

Sometimes called the “hoot owl,” the barred owl is named for the bars or dusky markings on its underside. It has a wingspan of up to four feet and is nocturnal, which means it is mostly active at night, when it can be struck by a vehicle while swooping down to catch prey. Their diet mainly consists of small rodents, but they will eat other birds, reptiles, amphibians, and just about any small animal they can catch. Their call is loud and can be heard up to half a mile away. There is a common mnemonic for the barred owl’s call: “Who cooks for you? Who cooks for you all?” Whereas red-tailed hawks prefer open woods, edges, and fields, barred owls like deeper forests and coves. They raise their small brood in a nest in a tree hollow or snag.

Photo courtesy of GoldenBright Photography

Timber Rattlesnake

(Crotalus horridus)

Slow-moving, docile, and shy, timber rattlesnakes are pit vipers, which means they have heat-detecting pits on their faces that enable them to track warm-blooded prey, mostly rodents. By eating large numbers of small mammals, they indirectly consume thousands of Lyme disease-carrying ticks each year. Young rattlers may be eaten by coyotes, bobcats, foxes, skunks, and hawks. Snakes relish the stored-heat energy of rocks and roads, which can spell disaster when vehicles approach more quickly than the snake can slither out of the way. They can live up to 30 years. Females give live birth (eggs hatch internally) to an average of 6-8 young every 2-5 years. Due to habitat destruction and purposeful and accidental killing, they are declining throughout much of Southern Appalachia.

Photo courtesy of Peter Paplanus

Common Eastern Firefly

(Photinus pyralis)

There are more than 9,000 known species of firefly around the world. In North America, the one you are most likely to see is common eastern firefly, which is also called the “big dipper” for the J-shaped flying and flashing pattern the males use to attract females. Fireflies cannot survive when their habitat is destroyed—and roads built on top of their mating grounds are a death sentence. Fireflies often flash with a rhythm and sequence that is not unlike poetry. Because they communicate in flashes of light, human light pollution can affect their ability to locate each other and find mates.

Photo courtesy of Terry Priest

Wood Frog

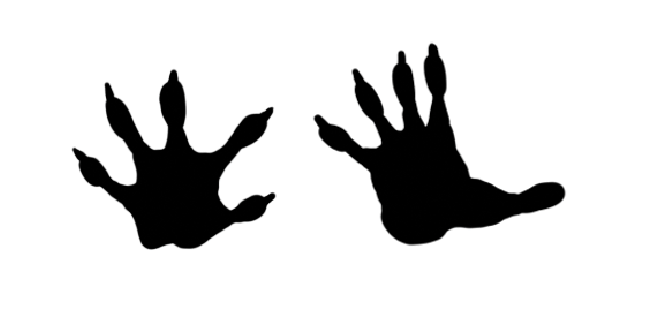

(Lithobates sylvaticus)

Frogs are fragile so changes in the environment can create stress for them. Wood frogs belong to the Ranid group of frogs that have large, strong hind legs for jumping, and are capable of traveling a mile or more to summer breeding ponds and over-wintering habitats. The wood frog has adapted to tolerate freezing of its blood and tissue during winters, when it deposits eggs in seasonal pools. Although some frogs remain fairly close to where they were born, wood frogs move out into different areas of the forest. This keeps their genes strong and diverse, but it can also put them in danger if roads are between them their desired new home. In some places in the US, groups of concerned citizens carry frogs across roads when they need to travel in great numbers to breed.

Photo courtesy of Warren Lynn

Virginia Opossum

(Didelphis virginiana)

Female Virginia opossums carry their offspring in a special pouch. This qualifies them as North America’s only marsupial. As the young age they leave the pouch, climb onto their mother’s back, and cling to her while she hunts. The opossum’s tail is adapted for grasping so it can carry leaves and twigs to line its burrows. Slow moving, short sighted, and likely to freeze in the face of danger, opossums are frequently killed on roads. Like the timber rattlesnake, one opossum can devour more than 4,000 ticks in a season, an important contribution toward controlling Lyme disease.

Photo courtesy of Richard Coldiron

Raccoon

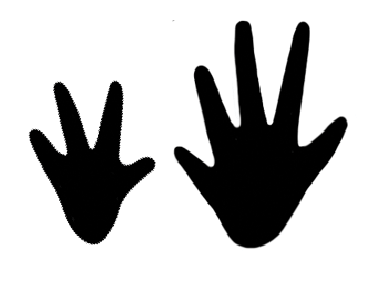

(Procyon lotor)

Raccoons are a common and crafty resident of southern Appalachian forests—and have secured a solid place in most urban settings as well. These masked and ring-tailed mammals are omnivores, eating everything they find on their nocturnal forages, from crayfish to blueberries. Raccoons can be seen washing their food in streams with their dexterous front paws. While captive individuals can live up to 20 years, raccoons in the wild rarely survive past three years of age, and vehicle injury is a major cause of their short life expectancy. Raccoons, with their exceptional night vision and climbing ability and agility, are capable of using a variety of structures, when available, to safely cross the highway.

Photo courtesy of Krystal Hamlin

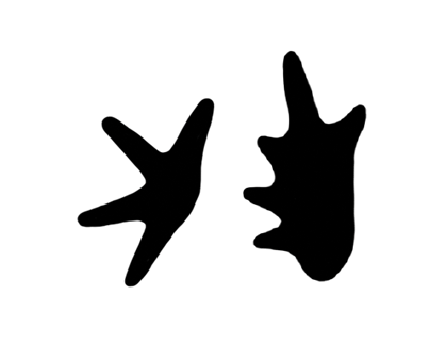

Red Salamander

(Pseudotriton ruber)

This bright orange salamander is “endemic” or restricted to the eastern United States, where it is common but threatened by loss of the habitat it needs in order to thrive. It is considered semi-aquatic and so is most successful in forested areas that have rivers, streams, and creeks. Red salamanders stay in springs or streams during the winter, traveling over land during the other seasons. They are most active at night, and large groups of them can be seen crossing roads together at certain times, which has led to concerned citizens stopping traffic to help them cross safely. They can also regenerate lost or injured limbs or tails.

Photo courtesy of Ashley Wahlberg

Eastern Box Turtle

(Terrapene carolina carolina)

The Eastern Box Turtle can retract into its shell and close itself off from predators. Damaged shells can regenerate and reform. Males have reddish eyes, while the females’ eyes are brown. Box turtles can live up to 100 years so long as they don’t get caught in a roadway when traffic is coming. Some individuals have been around since before roads infringed upon their ancient trails, so it’s easy to understand why these slow-moving creatures attempt often-futile crossings. They are especially active on our roadways during spring and fall due to more moderate temperatures compared to summer and winter. Females build their underground nests with their hind legs, and lay on average 3-5 eggs that typically hatch in mid-summer to early fall.

Photo courtesy of Great Smoky Mountains Association

Eastern Spotted Skunk

(Spilogale putorius)

This small skunk species has a distinctive black-and-white spotted pattern. It is slender and more weasel-like in body shape than the more common striped skunk. Though both species are famous for their unpleasant scent—released as a spray only when they are threatened or provoked—spotted skunks are also known for a defensive handstand behavior they use to intimidate predators. Conservation groups in Southern Appalachia are working to save the spotted skunk from extinction due to habitat loss and fragmentation. They are in the same family (Mustelidae) as weasels, ferrets, badgers, and otters. Unlike striped skunks, they are tree climbers. In the Pigeon River Gorge Study Area researchers have detected several occurrences of this elusive and increasingly rare species.

Photo courtesy of National Park Service

Long-tailed Weasel

(Mustela frenata)

Also known as the bridled weasel or big stoat, the long-tailed weasel has a small head with long whiskers and black eyes that look emerald green if seen by flashlight at night. In colder climates, their winter coats are white, but in Southern Appalachia, they are a buff color. This weasel’s scent glands produce a musky odor which, instead of spraying like a skunk, they leave behind through a process of dragging and rubbing over surfaces. Due to their high metabolism, they must eat often, and therefore are constantly on the move, sometimes traveling miles in one day in search of food (and mates too). Because they are secretive and hard to see, we don’t know how many there are. Researchers have observed several in the Pigeon River Gorge and are beginning to study them.

Photo courtesy of Matt Lavin