By Holly Kays | Lead Writer, Smokies Life

Editor’s note: This piece is the second of a two-part series exploring plans to rebuild I-40 through the Pigeon River Gorge and the project’s implication for wildlife populations in the region. Find the first installment here.

As the floodwaters of Hurricane Helene receded, they revealed extensive damage to Interstate 40 through the Pigeon River Gorge, promising that the rebuilding effort would be a top priority for the NC Department of Transportation in the years ahead. The agency has spent the past year exploring potential solutions, and now the plans are reaching their final form. The $2 billion project calls for a massive concrete wall— intended to stabilize the slope and protect it from erosion—that will run alongside the road for most of the 4.5-mile rebuild area.

Engineers see the plan as an innovative approach that will create a safe and stable roadway capable of standing strong against future storms. But members of the Safe Passage coalition, a group of organizations and individuals working since 2017 to reduce wildlife–vehicle collisions on the road, fear it will represent a generational loss for wildlife connectivity in the gorge—unless the plans are amended before implementation.

“It took ten years to get here, and it is a setback,” said Wanda Payne, Safe Passage’s liaison with NCDOT and a former Division 14 engineer with the agency. “But I think while you’re in that transition of ‘storming to get to norming’ in your process of development, there’s going to be losses and there’s going to be gains. And this is a hard loss, if [the final outcome] is going to be a loss.”

After the hurricane passed, Safe Passage had hoped for a silver lining to emerge from the storm clouds: improved opportunities for wildlife connectivity on the rebuilt road. But though NCDOT considered various ideas recommended by the group, ultimately federal reimbursement rules dictated the terms. Emergency funds from the Federal Highway Administration are available only for road “replacements,” not road “improvements”—and, according to FHWA, most things on Safe Passage’s wish list would fall under the latter category.

NCDOT engineers worked with FHWA representatives “every step of the way” to understand how various approaches might fare, said John Jamison, head of NCDOT’s Environmental Policy Unit. But even within that guidance, NCDOT has an incentive to act cautiously. The project isn’t slated for completion until late 2028 at the earliest, and federal reimbursements can take years or even decades to come through. Final approval for the funds could easily fall into the hands of someone who had no part in today’s conversations.

“You don’t want to risk Federal Highways saying, on a billion-dollar project, ‘Well you didn’t dot that ‘i,’ so you’re just out,’” said Payne. “And that’s what they could do, theoretically. So it’s a big gamble.”

These considerations led the design team to conclude that a massive retaining wall would be “the only viable option” for I-40, said Division 14 Construction Engineer Joshua Deyton. The extremely steep slope required a wall system, but the type of wall NCDOT had selected when repairing damage from Hurricanes Frances and Ivan in 2004 failed during Helene.

“That meant we had to put something back that was more resilient,” said Brian Burch, deputy program manager for design firm HNTB Corporation and former Division 14 engineer. “Two elements we decided would withstand Hurricane Helene and would allow us to build this wall-type system was interlocking pipe piles and roller-compacted concrete.”

Roller-compacted concrete, an extremely durable material used for everything from dams to container yard pavement, will form a wall along most of the 4.5-mile stretch, standing 20–30 feet tall and averaging 30 feet thick. An underground barrier of interlocking pipes buried 36 feet deep will prevent water from undermining the concrete edifice.

“Once they got the designs together, we saw there were going to be some major wall-like structures out there, extensive riprap in the gorge section, and we said, ‘What can we do to offset this?’” said David McHenry, NCDOT liaison for the NC Wildlife Resources Commission.

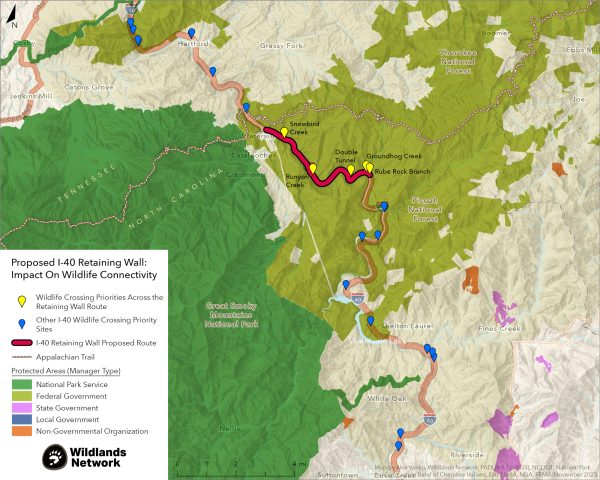

An agreement between NCDOT and the US Forest Service helped answer that question. NCDOT is taking road fill material for the project from nearby USFS land, and as a result NCDOT has agreed to several actions offsetting the resulting negative environmental impacts. The agreement includes four wildlife crossing projects on I-40, two of which—the double tunnel and Groundhog Creek—fall within the rebuild area.

Under the agreement, NCDOT pledges to install wildlife fencing at Wilkins Creek and build a ramp at the double tunnel allowing wildlife to again access the river where Helene had created an impassable cliff. The agreement also includes constructing wildlife passage facilities at Groundhog Creek and Cold Springs Creek “where practical and functional at locations proposed” in an unfunded 2024 grant proposal. Both sites contain multiple culverts, and the proposal called for adding benching or other material to create a dry crossing in one of them suitable for animals unable to navigate wet pipes, such as skunks, shrews, and snakes.

However, a 2022 research report funded by Safe Passage and created by Wildlands Network and National Parks Conservation Association wildlife biologists had recommended a different solution for Groundhog Creek: replacing the three smaller culverts installed there with one big culvert that even large animals like antlered deer could use. The report also recommended adding a dry crossing and creating a natural creek bottom in the culvert suitable for aquatic creatures.

“That has yet to be determined whether they will be replaced,” said Marissa Cox, western regional team lead for NCDOT’s Environmental Policy Unit. “My understanding is they are currently under investigation right now and no final decisions have been made as to any replacement or repairs or extensions of those pipes.”

The road design team, together with NCDOT and NCWRC officials, recently visited the gorge to review potential sites—which include “any tributary where dry passage may be possible”—with a follow-up meeting scheduled soon, Cox said.

Replacing the culverts would be extremely expensive, said Division 14 Engineer Wesley Grindstaff. They’re too deep to be replaced through a cut to the road’s surface, and the boulders used to fill the slope in the 1960s would complicate a horizontal approach. Because the culverts remained intact during Helene, federal funds would not cover their replacement.

The NCDOT–USFS agreement also includes several projects outside the I-40 corridor: a new bridge at Buzzard Roost Road to replace an existing concrete structure, which creates a barrier for aquatic species and is impassable to vehicles during high water; 8.86 miles of stream improvements to offset 1.3 miles of streams that will be “lost or permanently altered” due to quarry operations; and acquiring more than 1,000 acres of land, to be conveyed to USFS.

“We’re going to do what we can to do improvements where we can, and I think we’ve got a pretty good plan,” McHenry said.

If all goes as anticipated, the wall will remain part of the landscape for generations to come.

“The expectation is that whatever repairs we do this time, it will be permanent,” said Burch. “We don’t expect any other failures at that point.”

Without culvert replacements, Ron Sutherland, chief scientist for Wildlands Network and Safe Passage coalition member, is skeptical. During Helene, the gorge saw significantly less rainfall than other parts of the region, so the culverts running under I-40 weren’t put to the test like those in other areas.

“If we get a good strike from a hurricane that hits the Pigeon River Gorge local watershed, as steep as it is, it’s going to overwhelm those culverts,” Sutherland said.

NCDOT did design the new road with strengthening storms in mind, Grindstaff said. The agency typically builds new infrastructure to withstand a 100-year flood event, but Helene—in the gorge, considered a 500-year event—was used as the baseline comparison for the rebuild.

However, in much of the region, Helene brought on a 1,000-year flood or worse—though that term is a misleading moniker. It describes probability, not frequency. A 500-year flood, for example, is an event that, based on historical data (not forecasted future trends), has a 1 in 500 chance of occurring in any given year—0.2 percent annually. Likewise, every year there is a 0.1 percent chance of a “1,000-year flood” occurring. Helene’s arrival in 2024 has no bearing on the probability that a similar flood might occur in any subsequent year.

Especially in a warming climate, unlucky dice rolls are increasingly common. Parts of Western North Carolina saw a 100-year flood in 2004 after Hurricane Ivan came close on the heels of Hurricane Frances, and again in 2021 from Tropical Storm Fred. Then Helene landed in 2024.

“These weather events, as far as the intensity, seem to be greater over the last many years,” Burch said. “The intensities of the storms are greater, and they’re more frequent. So working with our federal partners the decision was made: Let’s try to build something back that’s going to withstand the next Helene.”

Regardless of whether the DOT meets that goal, the finished road will be a complex structure that won’t offer much opportunity for wildlife-oriented retrofitting once complete—though opportunities remain in other parts of the gorge. The 2022 report listed multiple priority projects outside the 4.5-mile stretch slated for reconstruction, and NCDOT “depends on and appreciates and utilizes” those recommendations, Grindstaff said.

The issue of wildlife crossings has come a long way since Safe Passage began. Despite Canada and Europe having made wildlife mitigation part of road building for the past half-century, as recently as a decade ago the issue barely received a passing consideration from road planners in the Southern Appalachians. But now—despite the unique constraints influencing the I-40 rebuild—road ecology is becoming a standard topic of discussion.

And, increasingly, funds are available to address it. In 2023 the NC General Assembly appropriated $2 million for wildlife fencing and related projects in the Pigeon River Gorge, and the body is considering an additional $10 million in its next two-year budget. In 2021, Congress authorized $350 million for the Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program—to be distributed as grants in fiscal years 2022–2026—and a bipartisan bill has been introduced seeking to extend the program. At both the state and federal level, the issue is gaining momentum. Payne likens the change to the rise of bicycle lanes and pedestrian features. Once seen as optional add-ons, they’re now integral parts of road planning.

But the planned wall would be a loss for wildlife that can’t be replaced by improvements elsewhere, Safe Passage advocates say, maintaining optimism that additional mitigations can be incorporated before it’s too late.

“We’ve got a window of opportunity,” said Jeff Hunter, NPCA’s Southern Appalachian director, “and I would hate to see that window close.”